After the wind, cold, and beauty of Patagonia, we headed back to the steaminess of Santiago for a few days, both to do a bit more touring and to watch the Super Bowl. It got up to about 95 degrees in the afternoon so even with the “on off” bus, it was pretty brutal. We finally made it up to see the statue of Mary of the Immaculate Conception that was beautiful in-and-of itself, but it also provided a panoramic view of the city. While the smog was fairly bad, people were out in droves bicycling and hiking. Once a month, they close down many of the streets to make it easier for the bicyclists to get around. As far as the Super Bowl is concerned, let’s just say it was a game, and not a very exciting one at that.

The next day we were on our way to Easter Island, a 2200 mile, 5 hour flight from Santiago. After arriving in rain, we settled in to our hotel, had a quick swim and were off to start our explorations. But why come to Easter Island? I have always been interested in the story, myths, and mysteries of this magical place and was more motivated to come after seeing the movie Rapa Nui in 2004. The story of Rapa Nui (called Easter Island by the Dutch explorers who arrived on an Easter Sunday) is a part of the larger story of the grand Polynesian migration, thought initially to have started in China (or Taiwan), through Melanesia, then Micronesia, and finally into Polynesia. Actually, the settlement of Rapa Nui was relatively late in the migration, starting about 1100 years ago. But like all other Polynesian migrations, the people who settled there traveled in two double-hulled, double-masted, nearly 300 foot long canoes filled with the tools, animals, and skilled people to colonize the island. Over the next 900 years, Rapa Nui would see rapid growth and significant cultural development, followed by internal strife leading to civil war, together with the destructive impacts of outsiders who brought diseases and took slaves. After reaching a peak of nearly 15,000 islanders broken into clans and tribes, the population plummeted to just over 100 people — total societal collapse. With the arrival of the Catholic Church, and ultimately being annexed by Chile, the population started to grow to the 8000 people that live there today. But the traditional Rapa Nui people today represent less that 40% of the overall population. For much of the time of Chilean control, the Rapa Nui people had little say in their future or the control of their own island. For years, the entire island was leased to a Scottish sheep ranching company and all of the islanders were forced to live in the main town of Ranga Roa, losing touch with their land and heritage. It has only been recently that the Rapa Nui were afforded full citizenship rights and today, they administer the national park that represents over half of the island’s landmass. After years of just struggling to survive, it is the young generation that is promoting a resurgence of pride in their Rapa Nui culture and heritage.

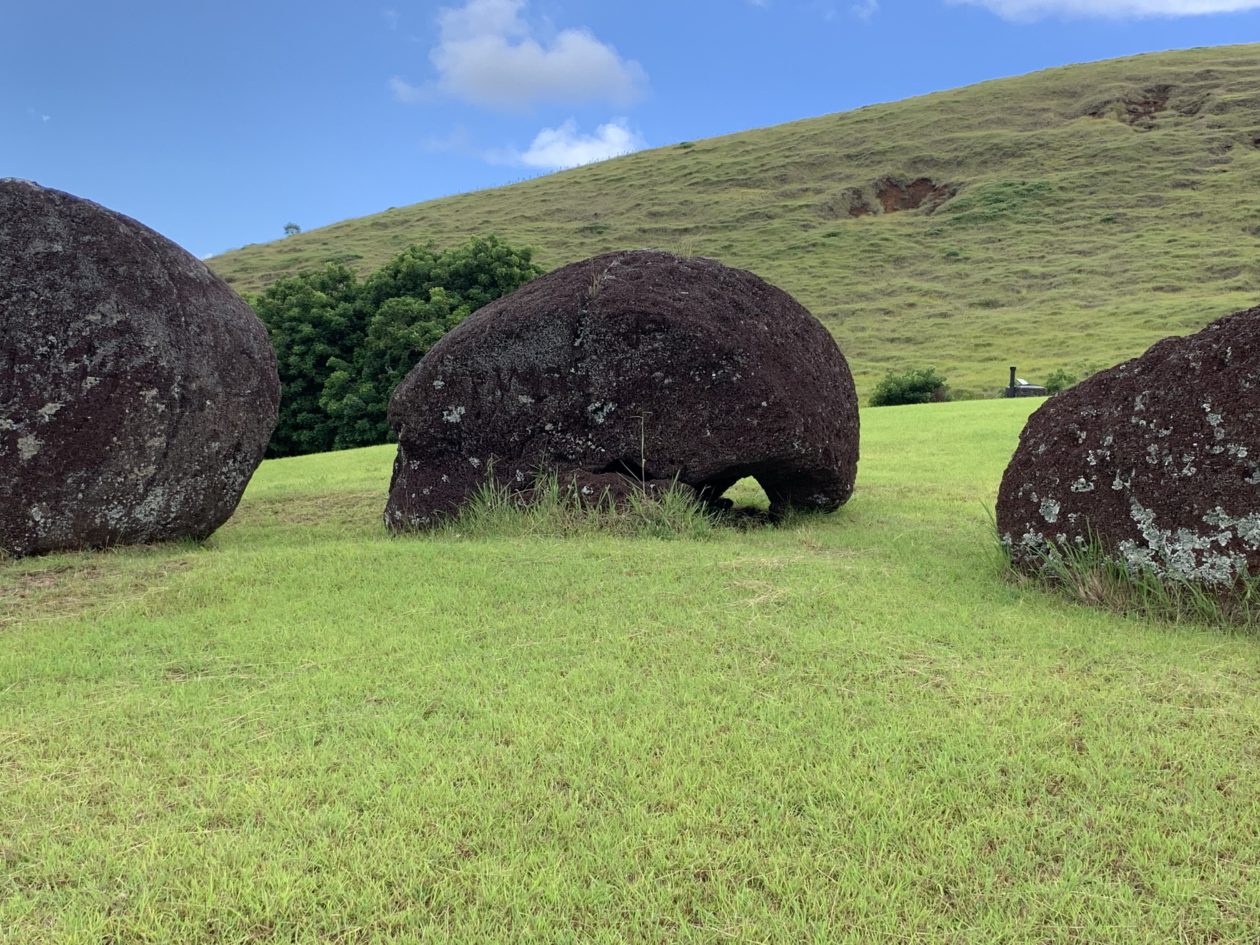

In our three days on Easter Island, we visited many of the historical sites there. We were really trying to understand the evolution of their culture and spiritual/“religious” belief system. There are really two (somewhat overlapping) stages that defined the Rapa Nui during their rise — the first symbolically characterized by the ahu (large stone platforms that often served as tombs for their ancestors) and the familiar moai statues and the second, the birdman clan (the subject of the somewhat controversial movie Rapa Nui in 2004). Underlying both of these phases was the power of mana, a spiritual energy that came from the gods that gave those who had it strength and power. For much of the time of the cultural development of the island, people believed the best way to access mana was through their dead ancestors who lived in the underworld where the gods were believed to be. Hence, within each tribe, revered ancestors were buried in the ahu and often the moai were the means to channel that mana to the family. Interestingly, the focusing agent was the eyes of the moai (made of coral and obsidian). Moai without eye sockets or eyes weren’t “alive” and hence couldn’t channel the energy. The moai were carved mostly from volcanic tuff from one quarry on the island. But then they had to be transported several miles to the villages where the ahu waited and then hoisted into place. Unlike portrayals in the movies, this work was not done by slaves. Rather this was part of a bigger barter system on the island, where carvers would trade their labors for other goods and services. But over time, conflicts started to arise — hardships would occur and tribes and families became more and more angry at each other. Bigger and bigger ahu and moai were built to try to please the gods; somewhat to no avail. Then open conflict began. One of the tactics was to have one tribe tip another tribe’s moai over (hopefully face down to block the flow of mana) and destroy their eyes. This was also accompanied by a rise in cannibalism, both because the Rapa Nui were beginning to starve, but also to take on the mana of the conquered warrior.

But also during this time, a different belief system started to emerge — the birdman cult. The thought was that the gods were no longer speaking through the islanders’ ancestors and that instead, migratory birds coming from the nearby island of Moto Nui were the channel to the gods. Hence, the ability to be the first to capture the egg of the first of the migratory birds to arrive would capture the mana. This involved an annual ceremony where “champions” selected by their clan leaders would race down steep cliffs, swim a mile to the island where the migratory birds would nest, take an egg and carry it in a headband made especially for the purpose, then swim back and climb up the cliffs to deliver the egg to the leader. The first of the leaders to get the egg was then the birdman for the next year and could make all the decisions regarding the governance of the island. What about the “champion” you might ask? They were actually banished to the quarry for a year to minimize any danger of him having too much power himself. Seems kind of unfair, doesn’t it? While that was a hardship, the consolation prize was having three young native girls taking care of his every need! But at the end of the day, this was all about a culture that outstripped their resources, with the destruction of their ecosystem and the subsequent internal struggle for survival. Yes, the advent of visitation and settlement from Europe introduced foreign diseases and the Peruvian slave raids had an impact, but this was a culture and society that had already collapsed.

Visiting all of these sites required a lot of hiking which made us feel less guilty about the evening Pisco sours and desserts. Did I mention that Chileans have a real sweet tooth? I should mention that some of what I just described is based on theory. There are multiple camps, encompassing explorers, scholars, and islanders who all have strong feelings about how things went down on Rapa Nui. There are at least five (passionately defended) theories on how the moai were moved around the island. There are also two camps (“collapse” and “anti collapse”) that describe how and why the Rapa Nui people declined so rapidly. As an example, there is a raging controversy over whether the many obsidian blades found were for cultivation or killing. One side took a series of the blades and had them tested for DNA on their surfaces. They found plant matter and no flesh or blood. Of course the other side says that they only took samples from fields so of course they were associated with agriculture, but there were many other examples not tested. Anyway, you get the picture. On the one hand, it is intellectual masturbation, but on the other, it is important for the younger islanders who are trying to rebuild history and pride for their culture. And speaking of culture, we were fortunate enough to be on the island during the annual Tapati Festival, a 10-day celebration that includes a wide variety of crafts, singing, dancing, and competition. Of course the ladies were disappointed that they didn’t get to see the buff (sweaty) native men racing up a very steep hill with a bunch of bananas (darn!). Instead, we got to see the children’s dance and singing performance, a well-choreographed extravaganza involving about a hundred kids.

On our last night, we went out on a stargazing expedition. Of course, the southern sky is very different to that of the north, but there was absolutely no clouds or light pollution and the stars, galaxies, etc. were very prominent. We also saw a lot of shooting stars. The only disappointment was that they were going to take a time exposure of us in front of the moai with the Milky Way in the background and they had “technical difficulties.” Ah well!

We thoroughly enjoyed our time on the island. We met a lot of very nice people (both Rapa Nui people and others), learned a lot (including dispelling of myths), and enjoying some wonderful meals and hospitality. Both our friend (and partner) Ken and I dispensed ample free consulting advice (especially about establishing a non-profit to benefit the restoration and preservation within the national parks). I think (for the most part) they appreciated it. Anyway, this was another stop on our journey to better understand Polynesia and we look forward to continuing to learn. We are now off the the driest desert in the world — the Atacama in northern Chile!